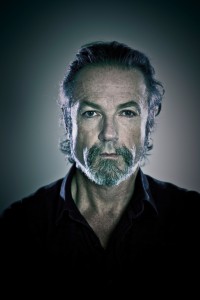

Steve Kilbey has been allocated room 1313 and he’s chuffed. It’s Kilbey’s favourite number. Right now he’s in the foyer of Brisbane’s Hilton. Later that night he’ll be interviewed by Robert Forster at a sold-out event at West End’s Avid Reader to discuss his new memoir, Something Quite Peculiar. Looking in rude health, Kilbey stashes his guitar case behind his chair, orders a herbal tea, and settles in for a chat with Sean Sennett.

I thought it was interesting that in the book you went right back to when you saw the Easybeats as a child. I can’t imagine how powerful it would have been for an 11-year old boy to see that.

At 11-years old, it blew my mind, so I immediately wanted everything that was in here, as I said in the book. I wanted to be doing that. Who wouldn’t? Seemed like I was the only boy in the audience, as well. They were my favourite band. I loved their songs. I had them all as singles, and then It’s 2 Easy came out and they were all on the one thing. Even at night when my parents would turn the record player off, I used to lie next to the record player just doing it manually, and listening to the music coming off the grooves. That was the only album I ever bought. I guess I drifted away.

Kids move on, don’t they? Writing about that period in your life, did you feel it took you back there? You revisited it?

Oh, totally. The whole process is Hardie Grant come to you and go “Do you want to write a book?”

“Yeah.”

“You reckon you can?”

“Oh, yeah.”

And then they go “All right, here’s your first bit of the advance. Start writing.”

And then you go “I’m going to write,” and as you start writing, you start going through the things I thought I was going to talk a lot about and then other things, that didn’t really occur to me, I started writing a lot about. Some of the things really took me back there, which was good. Some of the other things took me back there, and I’m going “oh no, I don’t want to fucking go back and revisit this stuff again”.

Was there a discipline where you come to a point where realise you have to move on from writing about childhood and move the story forward?

An editor came in and when it was disproportionate ‑‑ my mission was to keep it sort of about the music. They don’t want just a series of anecdotes. When, in my original manuscript, it threatened to go too far one way – it got trimmed. I could see at the end, looking back at it, I’m glad it got trimmed. Now it’s a better read.

It feels very cohesive and I guess a tight read. There seems a moment in the book where you become Steve Kilbey, the public version of Steve Kilbey. It’s odd to think of you working at the Paddington Markets, selling clothes. But you can feel there’s a destiny in the story, isn’t there? Did you feel that way?

Oh, yeah. I always knew it. I knew I was going to make it sooner or later. There was nothing backing that up except I could say ‑‑ like, I want to get into politics. I’m seriously thinking about it. People say “What do you know?” I go “I might not know much, but I fucking got to be better than this.” Obviously, and that was how it was in music. Okay, I’m not the greatest in the world, but Jesus, I can be better than some of the stuff that’s out there now.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote that book [Outliers] about people having to do 10,000 hours working before they become proficient at something. You certainly did your 10,000 hours whether it be playing bass in cover bands or recording in your bedroom. What was the learning trajectory like? Did you feel you were grasping it quickly, or was it a slog, or just endless hours learning things?

It was like learning a language. It’s about perseverance, or learning yoga, or learning judo, or whatever it is. Long periods where nothing is happening, just slogging away, and then one day you sit down and go ‑‑ where did that come from? It’s like the culmination. It’s a constant period of climbing a bit, plateauing, and then a sudden jump, and then plateauing all along.

I would say because my father was a musician, and his mum and sister were musicians, and his Uncle Joe was a musician, I think there was music in my blood. But I wasn’t an extremely naturally gifted musician. I didn’t just pick it up. There was a lot of ‘keep going with this’. I have to fight ‑‑ anything I’ve got in music I’ve fought for. It hasn’t just been a gift. I’ve worked for it, or thought it out, or kind of tried to make it happen. I’m not like Jeff Buckley that sort of one day picked up a guitar, had a beautiful voice, and was writing beautiful songs. That isn’t me at all.

The stuff about your dad is very evocative, really. It’s quite beautiful the way you write about him. He obviously had a big impact on your life. I liked your dad’s line about “The only intelligent thing about Bolan was that he could spell Tyrannosaurus.”Did you feel your parents had a belief that you would carry on with your dream and do what you’re doing?

No, they didn’t.

Was it too alien for them?

No, they didn’t really care. They really didn’t care what I was going to do. I wasn’t telling them all the time I’m going to be a pop star. They would have seen it more about layabout youth lying around listening to records, strumming a guitar. As a symptom of the kind of slackerness I was trying to pursue.

In terms of your process for the book, was it a case of putting all your other work to the side while you did the book?

No. It was like I’d get up and go ‘I’ve got to finish this song for someone; I’ve got to do this commissioned painting for someone; I’ve got to work on my book’. I’d go down to the pool, have a swim, come home and smoke a joint. And sit there ‑‑ either ‘which is my conscious the most guilty about, or which is the most appealing thing for me to do now?’ Some days I’d do all book and some days do all painting. Other days, I’d mix it all up and do a bit of book, bit of painting, bit of writing.

I didn’t have a big master plan and once again I have to say I’m amazed by how the editing process whipped my book from a kind of yeah, sort of a jumbly, mumbly sort of thing and and pruned this hedge of wild stuff back. Now it seems to have more purpose. I feel like I can’t really take the credit for it so much, because people have come along and have subtracted stuff from it that has made it much better, which I couldn’t see at the time. I’m thinking this should be in my book, and someone else had to go “No, that shouldn’t be in your book. Trust me.”

When you discuss your songs, you say they’re providing a guided meditation for the listener. How does that work?

It’s like the idea of with this music, and with these words, if you listen and think about it, you will sort of go into your own world. These things, these ideas are meant to be something… you can’t think about them because they’re not anything tangible. They’re kind of ideas, and they’ll make other ideas appear in your mind.

So when I listen to Marc Bolan, what I’m getting off on is the implications I’m finding in there. He’s just setting stuff up, shooting ideas out into the void, and strangers are catching them and going “Oh,” and if you really love it, with the music, you’re sort of seeing these scenarios in your mind. You’re engaging in these adventures. Every time you listen to the song you’re back on that landscape that he’s singing about. Hanging out with dryads and driving a Jaguar, and that’s what I liked, all those contradiction.

For example he was resolving things I didn’t think could be resolved. I loved ancient Greece and I love dryads, fawns, and satyrs, and the gods. But I love rock and roll and I was sitting there going this is a gulf that you cannot ‑‑ these two things, I feel like [they] could belong together, and then suddenly Marc Bolan showed me how it could be done. He’s going and singing about the gods and the fawns and the dryads and Narnia. And he’s fucking rocking, and he’s sexy. And I’m like wow, I can resolve these things in my life that I thought were unresolvable.

Of course, at 16 I wasn’t thinking in those terms. That’s something when you’re old you look back and go ‑‑ like a grammatical who’s looking at grammar and going ‘he’s used an adverb, and a verb, and then he’s done this ‑‑ and this is a participle clause’. But the writer himself wasn’t aware. If you’re writing a book, first of all in your life you did these things, and had these vague feelings that were propelling you towards what you wanted to do. Then later on, if people ask you to, or it’s necessary, you look back at it and give it this analysis. I was doing this, I was doing this. But at the time, I wasn’t thinking Marc’s resolving contradictions. I was just suddenly attracted unbelievably to a guy who was combining these things.

A couple of your own records you write about. Heyday you write about at length compared to other albums you’ve made. And also Séance. With technology now, do you ever think to yourself, given what you’ve written in the book, I’d like to go back and fix Séance? Or once you’re done as an artist, it’s over and done?

It’s over. If somebody else wants to, if someone said I want the tapes from Séance, I’m going to do it the way I want it to be done. I’d be like “Yeah, go ahead and do it.” As far as me, 30 years ago, I don’t give a fuck.

I guess Let It Be…Naked, McCartney couldn’t let it go. He had to go back and remix the whole thing. And I still like Let It Be more for some reason, just because I heard it first.

I liked George Harrison’s album the way Phil Spector did it as well. I think they’re exercises in futility but if you’re the Beatles and know that you’re going to go back and do an album that’s going to see another 80 million, maybe that’s the reason to do it. For me, to go and fuck around with Séance for two months, why? So 500 people can go ‘ah’.

Heyday was like a really big record in your life. It kind of feels like it was the end of one period and the start of another one.

It was. It definitely was, totally.

Was that the first record the band started writing as a collective as well?

More or less, there were sporadic things before that. We just decided ‑‑ Peter says it was his decision, I say it was my decision. But, we decided we were all going to write together, and we broke through a kind of artistic ennui that we were suffering from. We were kind of working with producers and they were trying to modernize us a bit, and we were lost. And I’d make these demos at home. They were pretty good demos and then I’d bring them in the studio and all we were doing was trying to recreate my demos, which wasn’t my intention. The drummer was playing exactly whatever pattern I had on the drums. And things were getting staler and staler.

We went to Perth and did this week in Perth, and we had 20 or 30 people each night, going, “You guys are so fucking washed up. There’s this new band called the Triffids. They’re a real band. You guys are so last year’s thing. It’s over. Why don’t you give up?” That was the basic message from everything. Literally people were saying that and figuratively in the non-attendance.

We made Heyday and I remember Perth as a yardstick for that. We did a week in Perth, and every night it was people falling out of the roof, going nuts. With one album, and the reviews were going, suddenly there were a whole new bunch of guys going “Wow! Fuck! Look at what these guys are doing. Just when we thought they were fucking finished.”

I thought the freeform piece in the book really kind of caught the drudgery of the road. Was that you just decided you were going to try that trick once in the book? Did you contemplate doing more of that? You’re known for that in terms of your blog and your poetry.

Actually that freeform thing was in another book of stories on the road. I suggested to Hardie Grant, I said, “I want you to read this thing. See what you think of that.” I didn’t think I’d really done it very well. They said, “Yeah, let’s put that in there.” It can divide the two halves of the book.

On one level I think I’ve demonstrated throughout the book there’s this kind of Cockney geezer going “Oh, wow, gee, I’ve got a Roman girlfriend. Oh, now I’m doing heroin. Oh, now I’m a rock star. Now, I’ve got nothing.” There’s this same idiot kind of looking out.

The modern world is full of Twitter, social media, Facebook, blah, blah. Is that a drag for a guy like yourself, for an artist trying to work?

I’m trapped. I waste my time on Facebook like everyone else. I’m putting pictures of my dinner out there. I go to a good vegan restaurant, I’m fucking going “Here’s my veggie burger.” All the stuff, pictures of my kids, pictures of my cat, and getting on there and going “I got a letter from the school saying Scarlet’s the best student they’ve ever had. How’s that?” I’m doing all that stupid stuff. It’s got me by the balls like everybody else.

I put something on Facebook asking if anybody had any questions for you. Paul Clarke, the documentary maker, asked “What were AC/DC like when you saw them?”

I saw AC/DC a number of times. I saw them at the Deacon Inn with their original singer Dave Evans. Each guy in the group had a costume. Malcolm’s costume was a Keystone Cop. Angus was a schoolboy. But he had a satin ‑‑ he was really a dressed-up schoolboy. Dave Evans might have been a jester. There was about seven people there – it just seemed like a rock band from Sydney that had a pretty good guitarist dressed as a schoolboy. Later, about three times, I supported them when Bon was in the band, when they came to Canberra.

As The Church?

No, as Baby Grande. And they were sort of good then. They had a shtick. The audience loved them. They loved them.

The heroin stuff in the book, in the final furlong, is very heavy. It’s hard to read. Was it hard for you to write?

Yeah. And it was a lot less than I thought. When I was dividing the book up in my head, I thought childhood, pop music, and then at the end heroin. And then when I got into the heroin bit I felt like there’s only two things you can really say about heroin. That is the great effect you get that makes people a junky, and the bad effect you get when you become a junky and you’re trying to stop doing it. That’s what people are curious about.

You can only tell that story so many times. You can only have so many I’m in the street in Stockholm, and a guy pulled a knife, and I’ve lost my money. The cops are coming, and I’m vomiting everywhere. I feel ashamed, and sick, and sweaty, and I can’t sleep. I’m in rehab, and blah, blah. There’s only so much you can write and only so much you can take.

The bit about heroin shrank a lot. And when I started it, I didn’t know where the book was going to end. It’s a funny book because it doesn’t ‑‑ apart from the outro bit which kind of sums up where I am now, it sort of has a strangely unsatisfying ending. It doesn’t sort of end. It just suddenly, when you think there must be a lot more to come because he hasn’t talked about this and this; suddenly it’s all over.

And then it’s rapidly compressed. Then I’m suddenly on the beach with two-year old twins going “Oh, I feel happy.” And then “Goodbye,” the book’s over. I’m off the gear: never mind about the next 20 years, see you later. Then a very short outro going “I’m on stage at the Opera House. Everything’s great. Here I am an old geezer, and my daughters are pop stars. See ya.” It seemed to me like I was going to write a lot more but in the end it accidentally ended up like this, and I think it’s all right.

Something Quite Peculiar is in book stores now. The Church have recently released a new album Further Deeper (MGM) as well a CD and DVD Live at the Sydney Opera House with the George Ellis Orchestra (MGM).