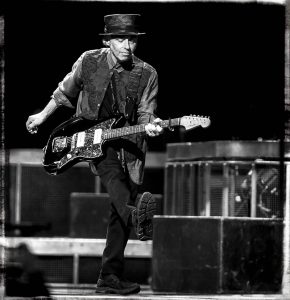

Pretty much every night on his recent Australian tour Bruce Springsteen would introduce the guitarist on his right as ‘the great Nils Lofgren’. It’s a fitting description for a man who has been playing music for over fifty years, either as a solo artist, a member of Grin or as a collaborator with the likes of Bruce, Neil Young and Ringo Starr. Lofgren has released a steady stream of solo albums over the years. Now, his best work – as a solo-artist and with Grin – has been collated into one of the most impressive boxsets this writer has ever seen, Face The Music. Spanning nine CDs and one DVD, the collection is a dream come true for the Lofgren connoisseur, the enthusiastic newcomer and anyone in-between. The set includes 169 recordings which stretch back to 1968, including 40 previously unreleased tracks and rarities.The accompanying book is helmed with an essay by esteemed rock historian Dave Marsh and then the pen is handed over to Lofgren, who has an incredible recall of time and place and …more importantly … how the music was made. Sean Sennett spoke with Lofgren about the box and other adventures that led to an enviable rock and roll life.

I’ve seen a lot of boxsets over the years. The packaging on Face The Music is fantastic, the design is seamless. Could you tell me when did the idea of the box first came up? What was your impetus for condensing your career in music into a box with this many discs?

I think it might have been 2009, we were working on Working On A Dream. I was based in New York with the E Street Band, and Fantasy Records got word to me that they wanted to talk to me about a project. Tom Cartwright was an A&R guy who used to work with me in the old days. I was a little stunned they wanted to talk about a boxset for someone who never had hit records. But then we got into the creative process, and they convinced me they wanted to do a thorough one. We settled on up to ten discs, including the DVD, and a book.

As they got serious about it, and it started evolving, my wife Amy got involved as artistic producer with the packaging.

The initial thing was you’ve got to go back and find rights to songs that are out of print. We’re talking about hundreds of songs, a book, this and that. Amy really took the bull by the horns, with all the creative peoples’ blessings. We looked at thousands of pictures. She finally picked that old picture of me and my band where we did the Hendrix/Cream imitation power trio. With Amy doing that and me agonizing over music for months and months, after two-and-a-half years of work with all these great people, to their credit, they got the rights to every single song I picked.

Early on, one of the selling points was we need some bonus tracks. I had like 100, so we picked the top 40. They were like oh, this is great. Just one thing led to another. After two-and-a-half years, we had a beautiful package we were proud to put out.

The discs sound so good. I’m wondering about the source material. You obviously didn’t have multi-tracks or quarter-inch tapes or half-inch tapes for everything. Did you remaster some things from vinyl? Where did they come from?

Whenever we could, we tried to get the original tapes from the record companies. Some items they lost, of course. Other times, some of the bonus tracks… Bob Dawson, who worked a lot with David Briggs, Neil’s producer and Grin’s producer, found old multitrack tapes. The piece de resistance to me was, we found a recording we thought was lost. I was looking for a cassette. I knew I had a cassette of a rough mix of Grin playing “Keith Don’t Go” with Neil Young on piano and vocals. I’d written that song on the Tonight’s the Night tour in ’73. I thought if only I could find that. But anyway, Bob Dawson found the original 16 track.

I insisted Billy Wolf was hired as the mastering engineer to master 50 years coherently; he’s a genius guy. Not only does he know me and my whole history, but you need someone that good to marry it all together from different tapes. Some of the bonus tracks came off cassettes. There’s a lot of tricks and stuff to get noise out. It was a lot of work, but Billy was at the helm of the music being married together.

Did you feel in a way you were curating somebody else’s work, or does it all feel very fresh to you, even though some of it is almost 50 years old?

To produce something like this you have to kind of be on the outside looking in. Still, it was so exciting and almost [to my] disbelief that someone would want to champion a project like this. For many decades, because of my affiliations, like working with Ringo or Neil Young or Bruce, I’d usually be able to call the latest president of Universal or whatever and say, “On the books, I owe you a lot of money for records that didn’t have hits. How about I buy 1,000 of my old records from you? You already have the art. It’s already mastered. Just print them up. Instead of a buck and a quarter, I’ll give you five dollars a record.” The answer was always yeah, it sounds good. Let me turn you onto our guys, and then those guys would be “it’s just too small potatoes for us”. Making money is small potatoes? They’d always say no.

I talked to lawyers about right-to-work clauses. They said you and a thousand musicians signed lousy deals in the ’60s and ’70s. Of course, you don’t have any pull. This is the consequence. No, you’re out of luck. They have the right to make you extinct. For Fantasy to come and resurrect that whole thing I was resigned to and accomplish it was amazing.

There’s a point in the book where you go way back and talk about your accordion teacher who says don’t play the instrument more than half an hour a day or you’ll get sick of it.

You’ll lose the student.

It sounds like this desire to get better was always in you, either as an athlete or a musician. That’s part of your DNA?

Yeah. The competitive thing is part of my DNA, but looking back now, I realize even at five, at every age of your life, you realize human beings wrestle with worry, doubt and fears. It’s human nature. And unbeknownst, now looking back, even at five and six, even though I had great parents, I’m still trying to be a five-year-old or six-year-old and music was therapeutic, healing, and a great escape.

In addition to loving music and being able to practice for two hours instead of a half an hour, not being burnt out ever, sometimes my parents would have to stop me. It was just like balance. You do your homework, go play sports, but you’ve got to do your lessons. I’d always err on the side of more. Looking back now, I realize it was therapeutic and some kind of healing I didn’t even know I wanted or needed to escape into.

Anyone who does what we do has erred on the side of being way too tunnel vision and putting too much time into it. It’s almost a requirement. But I was one of those kids at an early age, and bless them, my parents financed almost ten years of classical studies, which was an enormous backdrop when I picked up the guitar as a hobby. Two years later at 17 I hit the road with my band Grin, and just went on from there.

You had a hit with “Keith Don’t Go,” I know you’ve told the story before, but what was the inspiration for writing that song? It really resonated with people.

First of all, I was kind of a square accordion player. When I was 10 or 11, someone would play an Elvis or Jerry Lee, and I wasn’t emotionally mature enough to get it. So I would go oh, it’s just three chords, a little boring. I’ll pass. But by 12 or 13, the Beatles came out with the extra chords, the extra harmonies. Then the Stones hit and, then the flood gates opened.

Through them and the “British Invasion,” as we called it, headlined by the Stones and the Beatles, I discovered Motown, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Richard. All of that I discovered through them. And it was kind of like an epiphany that opened the flood gates for all of that.

It’s almost like why do I hear notes the way I hear them? I can’t speak for other great artists, but I think it’s like between my parents’ DNA, they danced as a hobby, all the time and played music in the house all the time.

So when their kids wanted to do any kind of music, they thought this was a healthy thing. They encouraged it and paid for lessons, which is a beautiful thing to have. Thank God, my parents supported that. But you realize after a while that, of course, you have to practice to put the notes you’re hearing together. How you hear them, where does that come from?

To me, I’m very down on organised religion. I believe in God, some higher power, and spirituality. So I thought wow, I’ve got this gift of hearing notes that has nothing to do with me. But what am I going to do with it? To have the encouragement, and of course, at a young age, someone like Neil Young and David Briggs take me under their wing. And all these people I’ve played with and worked with, and countless musicians that nobody knows about.

You realize, it’s kind of a calling. Then you realize that about performing. You realize after 10 or 15 years, okay, I’m starting to get a little homesick. But there’s this massive spiritual hit I get in front of an audience. That keeps you sticking with it.

I played guitar as a hobby from about 15. At 16 I started playing in bands. And back in middle America, nobody thought you could do that for a living. But you idolized these guys. One thing led to another, and by the time I was 17 I hit the road with Grin.

It’s interesting when Neil Young appears in the story, he’s still a young man himself. He was a mentor to you.

Yeah. It was interesting because it was right on the cusp of him turning into the super group Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Having the After the Goldrush record, after a great first solo album with “The Loner” on it and all these great songs. To take that ride with him, and be just this young 17-year-old that walked in on him at The Cellar Door in D.C. And it was touching. He had me out the next afternoon, just to hang out and get to know me at the hotel in Virginia. I watched four shows in two nights. My band had already planned to leave in three weeks to LA.

He said, “Look me up when you get there.” And true to his word, I did. That’s a whole other long story. But instantly David Briggs moved me into his home. And I started seeing them both daily, and a year later, we got the gig as the local band at the Corral, the local watering hole in Topanga, the famous nightclub there. Neil would jam with my band.

It’s funny. One day Neil and David jammed with us and we were so excited as kids. I go up to Neil’s house with David. It’s all a lot of fun for me and excitement with these guys. All of a sudden they say, “Nils, we’ve got to talk to you.” They were serious and I was like “What did I do wrong?”

They said, “No, you did nothing wrong. Your band is great. Your drummer sings great. You guys are really good. You’ve got to get a better bass player.” And like as a trio, there’s this camaraderie, and you’re always like oh, now, we’re on our way, and everything will be fine. Then all of a sudden somebody says you’ve got to dump one of your members.

It was like the big leagues. We figured out a way to do it. We probably didn’t do it as above board as we should, but at that point, I’d already left school. I was like I’ve got to make something go and happen. Thankfully, those guys were there every step of the way supporting me and inspiring me. But I learned so much from the two of them all along the way.

Apart from the boxset, you’ve done a lot of solo records in the last few years. Do you like to schedule things in between tours so you can go off and make a Nils record?

I don’t really, ever since what happened in the mid-nineties, when I started butting heads with my label creatively, and I realized, this isn’t a good situation. So I spent a year and a half getting out of that deal. With the advent of the internet, I realized, at that point, since I’m not having hit records that bring in money to give you power and control…. things, could be different. In the early days, the A&R guys pick a producer with you that you both like. The A&R guy would come by regularly just to make sure you and the producer were getting along, just low key. Good, that sounds great.

In the latter days, in the ’80s and early ’90s, all of a sudden, a guy would come by, an A&R, and it might be an accountant. I know it’s a cliché story, but he’d be like here’s five ideas. Pick three of them. It’s our money.

You felt like you were a psychiatrist to do what you wanted anyway, but I saw the writing on the wall. I got my freedom, and I got Dick and Linda Bangham to put a website together: nilslofgren.com And I realized at that point, thanks to technology, I needed to be a free agent. I’ve carried on as such since.

My big project this year is to write another solo record. Start recording it, but there’s no longer a situation where it’s “it must be out in fall, and you will tour in December.” There’s none of that. It’s like how’s my health? How’s my wife? How’s my family? And Amy is very supportive of my touring. She does the merchandize, art work and lots more, but it’s more free flowing and organic.

The first step, write an album and record it. That’s a big job. Obviously, I’m so in love with my job… but, if there’s ever plans for an E Street [project] I’ll be there.

For more information on Face The Music and Nil’s more recent solo work check out nilslofgren.com

Photo Credit: Cristina Arrigoni