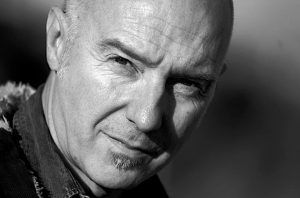

Punk. New Romantic. Sonic pioneer. Midge Ure has worn a lot of hats over the last forty years. He came to international prominence with his band Ultravox. He also co-wrote the charity single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ with Bob Geldof and set the Band Aid movement in motion. Now Midge is back on the road playing music from each segment of his career. The songs create a rich tapestry. Sean Sennett spoke to him recently, on the phone, from his studio in Bath.

Midge, you’re originally from Glasgow. One of Australia’s best known singers, Jimmy Barnes, recently wrote a memoir detailing what a tough place Glasgow was back then. A lot of great musicians have come from there.

Yeah, absolutely. A lot of musicians left Scotland and headed down your way. I think the AC/DC guys were from Scotland as well. I was just on the outskirts of Glasgow, so I was about three miles from the centre. It was rough and tumble. I was born and lived in the tenements, a slum one-bedroom slum, no heating, outside toilet, damp, and rats and stuff like that under the floorboards.

But I had nothing to gauge it against. That’s how everyone seemed to live that I knew. If you were out playing in a band, you had to be prepared to fight your way out at the end of the night because some morons got off and took a shine to you.

When you first moved to London, and fell in with the Rich Kids and so forth, were you attracted to punk, its’ ethos, or the energy of the playing? What was the lure for you?

I think, although Glasgow was only 400 miles away from London, it could have been a million miles away from London. It seemed that everything, especially at that time, was London centric. If you wanted to be popular in the music industry, it was always happening from London.

We just could see it, and smell it, and taste it, but we couldn’t touch it. So when I moved to London, it was with wide-eyed excitement about moving away for the first time and living out of home.

it was only 400 miles away from where I was born; I saw and experienced racism for the first time ever. There was a big campaign with all the bands in ’77 and ’78, the whole rock against racism movement. All the bands are playing these anti-Nazi league gigs, and I’d never seen any of that in Scotland. We had religion to fight about. We could fight each other about the fact that we’re from the wrong side of the fence, but all of a sudden, in London, this big cosmopolitan city it was a very vibrant, wild thing.

And my first day of arriving in London and rehearsing with Rich Kids, we went out that night, and we supported the Police before they became famous. And we went to a warehouse party where the Clash and Billy Idol and Siouxsie and the Banshees all hanging out. It was kind of baptism by fire. All these people I’ve read and heard about were all there. I was mixing with them. It was hideously exciting.

How did Malcolm McLaren come to pick you out and ask you about joining the Pistols?

Weirdly, the guy stopped me in the street coming out of a music shop in Glasgow was Bernie Rhodes who was the guy who went on to manage the Clash. He just said look, can you speak to my friend. I’m going to call him about a band, about music. I went around the corner, and the guy was Malcolm McLaren, which I have to say was a very odd sight to see in 1976 in Glasgow. This very effeminate looking guy with his dog collar and stuff.

He proceeded to tell me about his past dealings in the music industry and fashion industry, and told me about a band he was putting together and asked if I wanted to join. But he hadn’t asked if I was a musician, so I said, ‘No’. Who would ask you to join a band without finding out if you could do anything?

That wasn’t the point (laughs). The point was he was putting something together that was going to rattle the cages or shake up the system, and help sell clothes. It was more contrived than Bay City Rollers. It was very odd. I just walked away and said thanks but no thanks.

Looking at that period of music, you mentioned the Bay City Rollers. I just heard that great song on the radio, “January,” by Pilot. And then you think it’s only two years later you’ve got punk happening.

That’s how it was. And it should be now. It seems like there hasn’t been a young person’s revolution in music for 20 years. Dance music was the last revolution, the last thing that came along and threw songs out the window. It became all about the BPM and the sonic element of making records rather than writing songs.

So every generation should have a revolution. There doesn’t seem to be one. Back then, you would get the antithesis of what was currently happening. You had all the teeny bop bands, all the boy bands, and along comes the opposite, which are these rough, in all respects, bands coming out they weren’t great players.

They didn’t want to be great players. They had this attitude. They challenged the dinosaurs at the time by calling them dinosaurs. They were shouting down Pink Floyd and Lez Zeppelin, and whatever. It was with this cheeky arrogance.

Look at your career. It’s very interesting because I know you joined Thin Lizzy for a while. That would seem to be a certain road you could have gone down, but obviously, you had this yearning inside you to do music that at the time sounded like it was from the future.

I’d already been working on the first Visage album for nearly a year before I got the call to come and help Thin Lizzy out. I was never a permanent member. I’d been working on the Visage project, which I put together after the Rich Kids. I bought the synthesizer to bring it into the Rich Kids in 1978. It split the band up. It broke the band right down the middle. Half the band hated it. Half the band loved it. The half the band who loved it went on to form Visage. Visage was a studio conglomerate – one of which was Billy Currie, keyboard player with Ultravox.

During the year it took to grab studio time, to beg, steal, and borrow elements to try to make this record, Ultravox fell apart. I joined Ultravox, although nobody was particularly interested in Ultravox. It had the vibe that they were perceived as dead and gone. We were in the Vienna album when I got the phone call in the studio from Phil Lynott saying, “Can you come out. Gary Moore isn’t in the band anymore. Can you come and finish this tour we’re doing of America?”

I knew all the time I was coming back to my heart’s content, which was Ultravox. I was really excited about being in this band that nobody wanted because of the music we were making. It was ground-breaking, as you said, futuristic electronics with violins and electric guitar. It was this odd hybrid. That was infinitely more fascinating to me than as much as I loved Thin Lizzy, than joining Thin Lizzy as a permanent member.

I want to ask you about two songs. “Fade to Grey,” which you co-wrote, when you finished that song, know you wrote the lyrics for it, did you think, ’wow, this is really a piece of work that could make an impression’?

I think you know when you’ve got something that’s interesting. But you’ve got no idea I defy anybody to say they know when they’ve created a hit record. You don’t make a hit. You must make the piece of music and then someone else or a whole variety of someone else’s turn it into a hit record. That’s got nothing to do with the artist.

There was a feeling when we finished “Fade to Grey,” and I think the icing in the cake was putting the little French spoken words bit in the middle. It just seemed to give it that whole European flavour we were trying to capture at the time.

We knew we had something that was interesting but nobody saw it becoming a huge thing that it became. Exactly the same as with Vienna. We knew Vienna was interesting but it was so far removed from everything getting played on the radio at the time that there was a very good chance it would never get airplay, would never be played on the radio. Sometimes you’ve just got to stick your neck out and if you believe in what you’ve done and think it’s interesting, put it out there and see what happens.

Did you ever think about doing the vocals on “Fade to Grey” yourself?

I’m in there somewhere. Steve Strange was never a singer really. In order for him to sing a melody, I sang the vocals and then pumped the vocals into his headphones, so that what came out of his mouth was near enough the melody I was singing. Steve was more about the glam front man than an actual vocalist. So again, halfway through the whole project I joined Ultravox and that was where my musical leanings were going.

Visage was initially put together just to make my old Rich Kids friend Rusty Egan could play in clubs that Rusty and Steve were running in London. We were playing electronic music in those places, and we wanted to make music just for that.

When I joined Ultravox, Ultravox is very much a band, that was my band, that was my full-time thing. Visage was a learning curve for me. The first time I was allowed in the studio to make music that I felt was interesting as a producer. It was more a production vehicle for me.

It sounds in a way sort of you had to do Visage before you could really unleash yourself in Ultravox in terms of all the sounds you could pull. Vienna is a masterpiece in terms of not only the song and song writing, your voice; the production is incredible, even now.

Thank you very much. Again, I firmly believe that naivety has a massive amount to do with when you write certain songs. I think if someone had told us of what we were creating and what we aware about to create was going to be this monstrous record that would still resonate 35, 40 years down the line, we would have written a very different song because you would approach it differently.

You’d be trying to make it commercial. You’d be trying to make it appealing, whereas, we didn’t. All we did was just made something we thought was interesting. Maybe that naivety disappears after a while and you start trying to chase your own tail.

I’d like to think that doesn’t happen, but I suspect it probably does. When everyone around you is trying to talk you into writing Vienna Part 2, 3, 4, and 5, because they think it will be financially interesting, but you’ve said no; the next album we’re going to make we’re going to go off to the German countryside, with no ideas, and spend three months in the farmyard making this really dark, depressing record. That’s what we did. We would avoid that trap of trying to recreate something we had innocently and naively put together.

When you wrote “Do They Know It’s Christmas,” was there like a Eureka moment where the song literally came together, and you thought I feel confident enough to take this to this amazing array of artists who are going to sing and play on it?

No. I wasn’t confident about it at all. I thought it was a dreadful song. It’s the weirdest song in the world. There’s no chorus. The structure of the song is ridiculous.

My task was to start with this ominous chime, this clang of doom at the beginning, while this kind of subtle African landscape is running through the music. And then finish with a kind of, as Bob said, we need something that sounds like Happy Christmas War Is Over. We need something to sing along to. We didn’t have the “Feed the World” bit.

So the task was to start with this clanging chime of doom, and finish with a sing-along pop song. It’s bizarre. It was an odd thing to do.When we took the artists to the studio, they had never heard the song before. So there’s a moment in the making of the video where I’m playing them the track so they can learn the tune, and it’s me singing on the multitracks, singing the demo so they could learn the song.

I wasn’t confident about it at all. But the moment I heard them adding their talents to it Paul Young opening up the song was just fantastic. Sting singing “the bitter sting of tears” fantastic. And I was standing next to Bono when he did the “Thank God tonight it’s them,” because on the demo I’d actually sung that an octave lower. It was kind of a throwaway line. But he grabbed it and turned it into something else. The moment they put their bits of genius on it, the whole thing started to shape up, and turn into what it finally became.

The concept for your tour, is is something you’ve played around the rest of the world, this idea of doing something for each period of your career?

I went back and looked through my entire catalogue, which I don’t do. I find it a painful process. Sometimes you can’t think what the hell you were thinking when you wrote the song. You’ve moved away from it so far. Other times, you’re pleasantly surprised.

I looked back over all the albums, 14 albums, and decided to play one or two from every album, including the obvious songs that people would expect to hear. But the entire set isn’t hit after hit. I’ve tried to choose the best representation a song that represents that particular album best, that works in the format we’re performing. We’re performing on this tour acoustically, so I’ve got these two young multi-instrumentalists, really cool players playing violin and mandolin and guitar and keyboards and all sorts of stuff. We’ve rearranged the songs to fit that format.

The interesting thing is although some of these songs are 35, 40 years old … even though we go back that far, and taking it right up to my last album Fragile, the way we perform then kind of glues them all together. It’s hard to tell which one was from which decade. They have a sound to them. There’s a coherence to them.

Midge Ure plays the Triffid (Newstead) this Sunday, March 12 2017 before heading off to New Zealand. Trevor Jackson speaks in detail with Midge about his Band Aid work here https://www.tommagazine.com.au/2017/03/04/midge-ure/