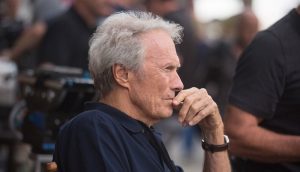

Director, Clint Eastwood, takes flight with Sully, the real life story of Captain Chesley Sullenberger (Tom Hanks), who became a hero after gliding his plane along The Hudson River, saving all of the flight’s 155 crew and passengers. Gill Pringle sat down with Eastwood for an exclusive chat.

At an extraordinary 86-years-old, Clint Eastwood is still in the heady midst of a very-late-career hot streak. Sure, he was big in the sixties and seventies with classic westerns like The Good, The Bad And The Ugly and The Outlaw Josey Wales and gritty urban thrillers like Coogan’s Bluff and Dirty Harry, but back then, Eastwood was solely a populist hero. His fans were the people who slapped down their hard earned cash at the cinema box office, and not the critics and cultural commentators of the day. To them, Eastwood was a right wing bully-boy making lowest common denominator movies for an undiscerning audience. Today, Eastwood now finds himself in an unusual position: occasional critics’ darling. With a series of intelligent, artful films (Bird, White Hunter, Black Heart, Unforgiven, Mystic River), the actor/director slowly but surely got critics on side, picking up a clutch of Oscars along the way. By the time his 2004 masterpiece Million Dollar Baby was awarded four Oscars (including Best Film and Best Director), Eastwood was in the Hollywood firmament, an icon both loved and respected.

Since then, he has continued to work hard and consistently, delivering the towering back-to-back WW2 dramas Flags Of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima; the surprise box office smash, Gran Torino; the fiery period drama, Changeling; and the South Africa-set Invictus. After a few near misses (Hereafter, J. Edgar, and Jersey Boys were all strong works in their own way, but failed to rally audiences and critics), Eastwood hit pay-dirt again with 2014’s hugely successful, and highly polarising, American Sniper. “Well, I don’t know,” Eastwood replies when asked how he drums up the energy to keep directing films at such a furious pace. “I guess that I’m not in front of the camera as much as I used to be. I feel like it’s a good time to be doing it.”

The director is now behind the camera for another ambitious, large scale drama with Sully, which stars Tom Hanks as veteran pilot Chesley Burnett “Sully” Sullenberger, who was hailed as a national hero in the United States when he successfully executed an emergency water landing of US Airways Flight 1549 in The Hudson River off Manhattan, New York City, after the aircraft was disabled by striking a flock of Canada geese during its initial climb out of LaGuardia Airport on January 15, 2009. All of the 155 passengers and crew aboard the aircraft survived. FilmInk spoke with Clint Eastwood just prior to the film’s US release.

How did the project first come to you?

“The script sat on my desk for almost a week. I was going home one night, and my assistant said, ‘Take these scripts with you. Look at the untitled script about the miracle on the Hudson.’ So I went home and I started reading the other scripts. She kept mentioning the script about the Hudson all week, so I thought, ‘I better read this!’ I did, and then I was thinking, ‘Why the hell wasn’t I reading this script instead of those other turkeys?’ I just fell in love with it right away. I thought that I knew all about the miracle on the Hudson, because I followed the news very carefully when that happened. Then all of a sudden, it made sense. The first thing that I started asking myself was, ‘What’s the conflict there? This guy lands a plane and saves 155 people…where’s the conflict?’ Well, Chesley Sullenberger went through all of these periods of self-doubt inspired by the national transportation society or whatever the hell it’s called. He had to actually prove his decisions, and they came out to be the right decisions. Then it became very dramatic, and that’s what I was looking for. My first thought was, ‘Well, this must be a wonderful event, but who wants to see a whole movie about it?’ Then we get to live through it and we have all the various emotions about all the characters and all the different attitudes that you have about that. Then there’s his family life, and how it affects him and his self-reliance. So it became a fascinating story in the end. All I did was add some things, like the dream sequences, so the viewer could see what it was like in his head to make those decisions.”

The media is so quick to label someone a hero, but Sully was always saying that he just did a good job. What’s your thought on heroism and professionalism?

“It’s certainly different compared to when I grew up. When you thought of heroes, you thought of someone like Audie Murphy…someone who was above the norm in a certain situation, usually in a war-type situation. It’s this whole politically correct thing now where everybody has to win a prize…all the little boys have to go home with the first place trophy. There are a lot of people who don’t get a chance to be heroes, but they are very important people. There are always people who do and are something a little bit extra, a little bit beyond what could be expected of them. People doing things on behalf of others is as good a way to be a hero as any. You think of Iwo Jima or someplace where some fella fell on a hand grenade to save his friends. You often wonder, ‘Did he do that on purpose, or did he just trip?’ I mean, it’s a very heroic thing to do. Most people could hardly fathom that. If most people saw a hand grenade, they would start running in every other direction, and I’d be right there pushing them out of the way, like, ‘Get me out of here!’”’

You’ve flown helicopters for a lot of your life – did that give you a different understanding of Sully’s achievements at all? And did you ever feel like graduating to airplanes?

“I might have flunked. I’ve flown helicopters for 30-35 years and I still own one. I haven’t flown it much lately because I’ve been doing films. It had an influence on me. I’ve always liked aviation. I’ve always been fascinated by it ever since I was a kid, but I never fell into it until later. But aviation is very exacting. When you go to fly every day, you have to check everything. When you get in your car, you don’t check the wheels, or the oil or whatever, every time you drive. We don’t care if the wheel’s half on as long as we get there by the skin of our teeth. In aviation, you just can’t do that. You have to be a very exacting person, and you have to be really good with detail. You have to live by the rules, and Sully is that kind of guy. He knew about the rules, but he never would have known that he would have had to make a decision about landing in the Hudson. All of a sudden, you’ve got to take into account all of these little things. That’s what the whole story’s about: whether he did have to or not?”

You’re a plane crash survivor yourself [In October 1951 during his military service, Eastwood was aboard a Douglas AD-1 military aircraft which crashed into the Pacific Ocean north of Drake’s Bay near San Francisco. Eastwood escaped serious injury and swam to shore using no help] – did that help you to understand better, as a director, what these people went through emotionally?

“It probably did, but I haven’t thought too much about it in recent years. It was a bit different, because it wasn’t with a group of people. I was just a passenger in a lone spot on the plane. I never knew at the time what he was doing. I was just guessing that he was gonna do a water landing. If he’d bailed out and just left me there, then I would have been in bad trouble. Fortunately, he did the right thing and waited for me. That was an experience that was different, but by the same token, it gives you an idea of what it’s like to get to that moment where you say, ‘This is it. Some people live through this and some people don’t.’ That was all that I thought about, and fortunately once we’d got in the water, I felt much better.”

Looking over your career, you seem now less bound by genres and narrative structures as you were earlier on, and more willing to explore different creative avenues.

“It’s just time…time goes on. Maybe it’s about spending more time behind the camera, and not being so concerned with film projects that demand my presence. I’m relieved of that. I don’t have to worry about what everyone else is doing. It’s just a matter of growing up…you never stop growing up – it’s what makes life enjoyable. You learn something new every day hopefully about yourself, about other people, and other actors. Watching other actors perform is very exciting for me.”

Stylistically, what was your approach to Sully?

“The story is very realistic, so the only thing that I decided to do was add the dream sequences. I didn’t want the landing to be only a few seconds in a 90-minute movie, and then spend 88 minutes chatting about it. The dream sequence is so the audience can interact with that more. If he hadn’t of done what he did, then it would have ended up a mess. If that river wasn’t there, it would have been bad. A lot of very lucky things had to fall into place for this to happen. But it did because the right guy was there to take advantage of it. There are a lot of what ifs. A water landing can be done if it’s executed right, but it can be very bad if it’s executed wrong. There are a million things that could go wrong if it wasn’t for good quality flying.”

Do you consider that you have a certain style as a director?

“When you’re reading a story, you’re thinking of it as a finished product. Then as you’re going, you start to think, ‘Well, maybe the finished product could use a little bit of this and that.’ It’s just what’s on the way after you put the script down.”

This feature is via our good friends at Australia’s best movie site, www.filmink.com.au – check them out now!

Sully is in cinemas now. Courtesy of Roadshow we have 5 in-season doubles to give away. To be in the running send an email to with Sully in the subject line. Please include your best postal address. Winners will be notified by return email. One entry per person.