Late last year the NGV launched one of the most talked about exhibitions in recent history, Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei. The exhibition, developed by the NGV and The Andy Warhol Museum, with the participation of Ai Weiwei, explores the significant influence of these two exemplary artists on modern art and contemporary life, focusing on the parallels, intersections and points of difference between the two artists’ practices. Surveying the scope of both artists’ careers, the exhibition presents more than 300 works, including major new commissions, immersive installations and a wide representation of paintings, sculpture, film, photography, publishing and social media. The exhibition explores modern and contemporary art, life and cultural politics through the activities of two exemplary figures – one of whom represents twentieth century modernity and the ‘American century’; and the other contemporary life in the twenty-first century and what has been heralded as the ‘Chinese century’ to come.

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei premieres a suite of major new commissions from Ai Weiwei, including an installation from the Forever Bicycles series, composed from almost 1500 bicycles; a major five-metre-tall work from Ai’s Chandelier series of crystal and light; Blossom 2015, a spectacular installation in the form of a large bed of thousands of delicate, intricately designed white porcelain flowers; and a room-scale installation featuring portraits of Australian advocates for human rights and freedom of speech and information.

The exhibition has not only taken Melbourne by storm, but Australia also. As the exhibition was about to open, director Tony Ellwood sat down with Ai Weiwei for a conversation which we have great pleasure in sharing here.

Tony Ellwood: I thought we’d look at your career and practice somewhat chronologically, so by way of introduction, I wanted to mention that your father Ai Qing, who was a well-respected and known poet, an intellectual who during the cultural revolution was exiled by the Chinese authorities, and sent to a labour camp when you were very young. Then later, with your family, was exiled to Xinjiang province for 16 years. You then returned to Beijing in 1976 where you enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy, and soon become an early member of the STAZ, which is one of the first avant-garde art groups in modern China. Weiwei, what motivated you to become an artist?

Ai Weiwei: First, I’m very happy to be here, and I will never dreamed I can be an artist like this. The motivation for me to be an artist it to try and escape from the political situation. I often said it’s a place I can hide because I grew up on very strongly political motivated society.

How did your father respond to you being an artist?

My father also will never imagine I will become a artist. He become very successful when he was very young. He was study in Paris, studying art in the 1930s. Admittedly when he returned to Shanghai, he was arrested. So in jail he become a poet. He never really encourage us to become artists because in China to be artist is always has been a dangerous position, and not only our family. There’s hundreds thousands, millions people only because they are either associated with art or have some or intellectuals has been the whole life has been damaged. So he will never imagine I will become artist.

Was it because of the difficulty of being an artist in China that you moved to New York in 1981? Will you tell us a bit about that?

Yeah. In 1981 is the year I decide to go as far as possible from China, and I start to realize it could be dangerous if I stay. That’s the year I was 23 or 24 years old. I see my generation, some young singers has been put in jail with very fabricated so-called crimes. The only crime is they want to speak out their mind and to be conscious about the future of this big nation. That’s simply is a crime. So I made a decision to escape.

What American artist influenced you at the time?

At the beginning, as every student, you have to struggle with language, the financial condition. US is a place which is not very it’s not a easy place to live, especially New York. It’s very tough place. But that’s what I want, to be a centre of the contemporary activities. And that’s why I lived in New York. But basically, I did my little study in Parsons School of Design, and then later I drop off, become kind of illegal resident in New York, because you have to keep this student status. Otherwise you’re not legal.

But since I understand one out of seven or eight migrants in Manhattan is somehow illegal so it’s nobody every bothered me of my status, which I really thankful for US being so general at that time. And I struggled as any new immigrants, get all kind of jobs, just to pay next month’s rent. And the rest of time go to galleries, museums, and doing nothing else.

When you were going around the galleries, Andy Warhol had quite a profound impact on you at the time, didn’t he?

Yes, Warhol is one artist has I think I’m most attracted to. Many young people very much are attracted to him. Mainly about his personality, his way to look at art, and his attitude toward art. Those I really have a really profound impact on me.

Did you ever meet him?

I saw him from far away, in the openings. If he’s there, you obviously hear people say “Oh, Andy is here,” but you don’t really have to meet him. He’s like air or some kind of perfume in the air.

You’ve had a very rich time in America, more than ten years. Why did you decide to return to China in 1993?

I think thousands of people, or maybe a lot more people at that exact time, New York have 60,000 artists, workers, waiters, or all kind of jobs. I simply realised New York doesn’t need me to be there. Then I realised my father getting very old. Since 12 years I haven’t really went back once. And so I said it will be last excuse for I go back to China to visit him.

Then while you’re there you’re given this very exciting commission with Herzog & de Meuron to design a major new stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, which was a project which radically enhanced your international profile. But it also changed the way that you saw China, and it changed your relationship with the Chinese authorities.

In addition to that, by 2011 you were arrested and imprisoned without charge for 81 days. That’s quite a tumultuous return for you. Can you tell us what happened?

It sounds very dramatic. It’s over ten years a period of time. A lot of things happened, and we just have to escape that, and yeah, I start to work in architecture, which get me involved in society. I was a very private person as a artist. You don’t know much what’s going on, but once you are involved with architecture you know, China was booming, and everywhere they build buildings. They realised this guy has very strong, clear opinion, aesthetics, or took a new identity to what we’re doing.

So I become some kind of spokesperson on the new ideas. But only in architecture. So I got involved with politics, politicians, planners, constructor, developers, and all level of society. And later, I got involved with the Internet. By 2005 the state-owned company opened a Internet blog for me. I said I never touched a computer. I don’t know how to type. So they said that’s fine. We’ll teach you. With your influence we believe it’s very good for Internet. I believed in them. I really falling in love with Internet. That dragged me into a deeper problem.

Because you were so outspoken.

Yeah. Once you start to see such a platform, it’s like miracle. You start to live in this kind of dream. You can really clearly state your mind, put your blog, and post it. So some of my articles immediately got [a] hundred thousand people reposting it. So that is become like a drug. You see how powerful that can be. You can reach out. You can hear the feedback, and it’s like a water starts boiling. It’s really amazing experience. Until they shut down my blog.

It’s shut down and you’re imprisoned as well. When you’re released you have your passport taken away from you, and for 600 days you can’t leave Beijing.

[It was more than] than 600 days. I’ve been putting the flowers in the bicycle for 600 days. But actually they take my passport away more than four years.

During that time, you’ve been incredibly prolific. You’ve had literally hundreds of exhibitions all around the world. But one of the things I think has been very affecting for the staff here too is knowing that of all these major exhibitions you’ve been denied the opportunity to sight them. So coming into Melbourne now and seeing “Forever Bicycles,” for example, that’s only the second time that you’ve ever seen one of your bike installations. That must be incredibly moving for you, having missed so many of those other previous opportunities.

First, I have to thank the person that realised how much the authority here and government helped me to keep myself not to attend all the openings, so I do not meet all the journalists like this. It saved me a lot of energy and so I can concentrate in doing my work with my studio people. But of course, it’s amazing to be like stage or see your work in reality, and to see how people responds to your work.

Amongst the work, this show, maybe 90 percent, I never see a single of them being putting up, under also many new works in this show. It’s first time being showing, so it’s a really very interesting experience. Just put me like everyone else, you know, to see a show, which could be mine, but you know, I’m not very familiar with.

In the lead up to the exhibition, you also had quite a high-profile issue occur with Lego denying you access to their product as a result of your work being too political. You’ve responded to this with a new work which we’ll see today, which is a work titled “Let Go,” which focuses on Australian human rights activists. Can you tell us about how this project devolved?

Yes. I always have a idea to produce a new work in relating to the location, the very specific area which is Australia or Australians and their every project for me is a possibility to learn what happened in that land and what is the struggle in there. And of course, the museum and TV provide me the information and a list that we go back and forth, examine the condition.

Now I see the work “Let Go” is a very beautiful work. It’s like a little temple in dealing of freedom of speech, or a temple for the consciousness. I’m very happy this can be possible, but of course, since happened like the company who makes those plastic refused to let us have it, to even say this kind of work somehow is kind of politics, they’re not going to support. Which I still feel is a mistake of them, you know, we’re talking about a very essential human rights, about freedom of speech. And if you really read those people, their mind on what they’re helping through, you really think they’re heroes of our time. You know, it’s people will really have to pay respect and we have to learn from them. I’m happy this happened and very proud of that.

We think it’s a very powerful work, so thank you for persevering with it. Final question I wanted to ask you; what does it feel like to have your work shown alongside Andy Warhol?

Again, this is like a miracle, and I’m very still unbelievable. Years ago I met Eric (ph.) in Miami Beach, and at that time we talked about having a show somehow, but we never imagined to have a show like this. During this many, many years of development, finally I see my work can be shown next to a true 20th century master, the person I admire the most, Andy Warhol. Which I am still shy to see my work next to it. I try to cover my eyes, like oh, you know, to see to pay more attention to his work. I strongly encourage other people also do so.

Thank you. Although you did say the other day that you couldn’t distinguish at times which was yours and which was Warhol’s. You said if it was a good work it must have been yours. You did say that.

Yes, sometimes you lost your mind.

Next week we’ll be featuring an interview with both Tony Ellwood and Andrew Clark on all things NGV.

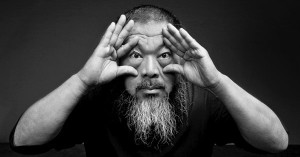

Photo: Ai Weiwei at National Gallery of Victoria exhibition Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, 11 December 2015 – 24 April 2016. Ai Weiwei artwork © Ai Weiwei. Photo: John Gollings