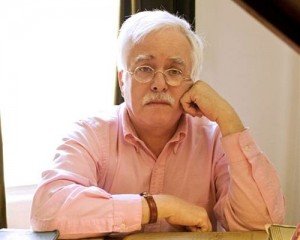

Van Dyke Parks remains one of contemporary music’s more enigmatic figures. Famous for co-writing Brian Wilson’s Beach Boys’ masterpiece Smile, Parks has earned a reputation as a fine lyricist, composer and thinker. On the line from his home in California last week, TOM bunkered down for one of the most engaging half an hours we’ve had on the telephone. Talking to Parks is like trying to catch lightning in a bottle. When the man’s mind starts to wander, you do your best to keep up. Parks visits Brisbane this week as a keynote speak at Q Music’s Big Sound Conference [2009], and he’ll be playing a one-off show at The Powerhouse. Besides ‘asides’ on everything from lunching as a boy with Walt Disney to reciting his lyrics for ‘Heroes And Villains’ into the receiver, here’s how much of the conversation transpired, a conversation lit by a slight southern drawl and punctuated by Van Dyke’s wicked laugh.

SS: Van Dyke, you mentioned that the first piece of music you paid for was Dean Martin’s ‘Memories Are Made Of This’ on a jukebox in 1953. You’ve seen a lot of changes. We’re living in the digital age now, and there’s a feeling that CD’s are coming towards the end of their term. How do you listen to music these days?

VDP: I think people weren’t really interested in the CD. I never got used to them. They broke and it was too small to read. It was painful to listen to for anyone who was around for the apex of the analogue age. That was a wonderful experience. The CD disappointed and they were too damn expensive. It wasn’t an icon like the LP in my era. I got everything digitalised. That’s something all good men and women should be doing in the community. If they hear stuff they like it should be digitalised. That is the migratory checkpoint for the future, if I may be so bold [laughs].

We have GPS now. We can tell where the bones are buried. If the island shifts, say Manhattan, and the graveyard moves, well, what archivists like to do is fix on what has happened. I think truly the business of music, or the technology, just didn’t serve well with the CD. It’s sad in a way.

SS: We’re living in a time now where great care is taken to re-issue albums. It hasn’t always been that way.

VDP: I remember meeting a person at a party and he had bought Warner Brothers old recording studios and he said, ‘I got all your stuff out there’. He didn’t use the word ‘stuff’, he used a harsher word. What he was telling me was, he has my life out there, the recordings, the big tapes. It turns out when Warner Brothers called to ask, things like Barbra Streisand, Duke Ellington, The Beach Boys and bottom feeders like me, we were all left behind. They had the two tracks and thought that was enough. They walked away from what really happened, which was a glorious age of recording where musicians crowded into a room and got used to each other. They made music of a quality and vibrancy that you just can’t hear today. I’m talking like a curmudgeonly old man now [laughs].

SS: There’s been a resurgence in people buying vinyl, where you have that terrific analogue sound and you get to hold a piece of art. What are you currently listening to?

VDP: I love any form of music. Right now I’m perched on some music that was saved on black cylinders in what we now call California in the late 19th century. They got it on cylinders and they just transferred it to tape. I got into this thing secretly many years ago, the folk idiom, I love folk music, and I find my obsession has continued. My favourite music is world beat, is that too vulgar an expression? I think what it means is, I have an elastic tolerance. I love a sound that has a drop of sincerity and optimism.

SS: You’ve worked a lot recently, doing everything from orchestrations for silverchair to film scores. Are you working on a new album of your own material? [In recent times, VDP collaborated with Brian Wilson on Smile in 2004, That Lucky Old Sun in 2007 and his own Orange Crate Art, with Wilson, in 1995].

VDP: [Laughs] You’re a harsh master. It’s like the good captain told me, ‘I couldn’t leave the cabin boys behind’. I’m saying, ‘Yes sir, I’m working very hard to get that record done’. I write songs. I’m at the age of 66 for Pete’s sake. I just can’t understand that. I used to be a brunette [laughs]. It was fun being a brunette. Now, beautiful women offer me their chairs. I would rather they just asked me if I needed to hold on [laughs]. I tell my kids, I point to my head, and I say ‘There may be snow on the roof, but a fire rages within’”.

SS: Where did all the time go Van Dyke?

VDP: I have had a great life. Music is all I know. I don’t play golf. I have a beautiful companion fox terrier; my present wife and I have been together for thirty-one years. It’s been a magical mystery tour. Atour de force. Time does fly when you’re having fun. I’ve had an eventful life, maybe not a public life, and I appreciate your encouragement.

SS: We’re looking forward to seeing you in Brisbane as part of the Big Sound conference, and, of course, at your show.

VDP: My engagement in coming to Australia means a lot to me, because I love what comes out of Australia and the astral skies. I’ve been there only once before. I love the national character. I love people to be direct and straightforward when they speak. I know I’m gonna get what I see in terms of human contact. They have a refreshingly un-neurotic nature [laughs]. Maybe I stayed in good hotels and I need to get out on the street. It seems like a wonderful place and that national character seems binding.

I keep talking about how I’m trying to reinvent myself. A new attitude to life itself is transformative; to really live life and embrace it. At the same time Australia comes along and, it might sound crazy to you, but I get the impression Australia is inventing itself for the first time. I get that when there is spasms of enthusiasm from Baz Luhrmann and so forth – there’s a kind of a [laughs] buckle in the swash. It all feels very frisky, and, I’m so ashamed to admit that I can’t remember some of the serious music I’ve heard from both Australia and New Zealand as well but boggling abilities are coming out [of these places].”

SS: How did the Q Music crew make contact?

VDP: I got this email inquiry. One day I was walking my dog and my wife was so happy that I was doing this for my health. I was out there walking as fast as she was. I have an alpha wife. She say’s ‘It’s good honey, I hope we both live long enough to use what it is we have learned’. I loved her for saying that. I think what is important is me to start offering, at no cost, what I paid dearly to learn. I believe I can do that in discussions with music. I wanted to offer that. I had no excuse not to do it. I thought it would be fun and that’s why I’m coming.

SS: You’ve spoken in the past about creativity being a lot of hard work and it’s ‘unwise’ for people to assume creativity is down to, or should reply upon, sheer genius.

VDP: I think it’s an important thing. What you do is, you get an offer to do something and this is what music is all about to me. I want to categorize the opportunity of music for a second. You get an offer to do something, and you’re like Moses, you don’t know if you can do that job. I’m under qualified to do that job. Because music is loud and people are going to hear you, there’s no shelter in it. You must do things, which are beyond common human comprehension or ability. They have to do with courageous resolve, the ability to trust in something completely abstract, the ability to be totally enquiring and, at the same, beyond the powers the prediction. You just have to put your shoulder to the wheel to get stuff done.

I’ve been in a world where they say ‘publish or perish’. I’ve been in a world of deadlines and I’m deadline oriented. They do have a joke down at the musicians union, ‘Do you want it good, or do you want it Monday’ [laughs]. Isn’t that great?

The thing is, I’m just saying it only looks easy this business of music, the abstraction process, it’s no different from any other of the arts. Basically it boils down to the fact that I have an immediate compassion for people who toil in this, I wouldn’t say thankless [job], but you don’t do it to get thanks or praise, I think you do it essentially for the catharsis, the great event of the great discoveries and the revelation in dangling in front of the creative process.

SS: You’ve just written lyrics for Ringo Starr. What’s new for you when you get home? I understand there’s a film score you’re working on.

VDP: I’m one of many people in a town of embarrassing riches of talent. I’m just about to start a Dutch film score. I want to get out of the hamburger connection. I want to do some modest films of European origin. I want to get noble and global all at the same time. I think that California, in terms of film, is a great yawn for me.

[Now], I walk into a room and I’m the oldest thing in the room, generally. I see the disadvantage. If you’re over 30 [in this industry] you’re suspect. Recently I went to a place where I wasn’t the oldest person in the room, I was the youngest. There was a bunch of old men sitting around a campfire and above the campfire they had a motto for their club and it said, ‘Old age and treachery will overcome youth and ability’. I looked at that, and I was very offended. Then I thought, ‘Wait a minute, that might be a good idea’. The reason for that is because veterans get treated like you-know-what by young bucks and by the industry. Our industry in America is totally ageist. I’m at the peak of my powers right now. I’m talking about in terms of what matters to the common wealth, the people around me. What matters to them is that I do what I what I do better than I ever have done and I make it a more worthy consideration to others. I have had a life where people have told me; more than a handful of people, and this stuns me, that my music has saved their lives. That’s enough to make a man weep. It’s almost like saying I may yet be necessary to someone in misery. I think about that. That’s why I lead to consoling in my work. Some people might think it might be a mile wider and an inch deep, but in fact, I think it better to be consoling.

One of my friends, Jim Ford, wrote a song, ‘Happy songs sell records/sad songs sell beer’. I believe I’m on the right track to what I do, which is to reinforce the validity of an informed optimism.

Sean Sennett

ENDS